To understand the phenomenon, imagine transactions that take months to complete like selling homes. A sample data set might look like this:

| Real Estate Data Set | |||||

| Address | Appraisal Order Date | Sale Date | Appraised Value | Sale Price | Percent Difference |

| 123 N. St. | 1/1 | 6/1 | 100,000 | 93,000 | -7% |

| 234 S. St. | 2/1 | 5/1 | 100,000 | 95,000 | -5% |

| 345 E. St. | 3/1 | 3/1 | 100,000 | 97,000 | -3% |

| 456 W. St. | 4/1 | 4/1 | 100,000 | 98,000 | -2% |

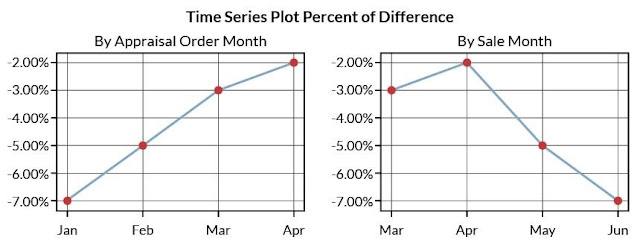

Note the difference in time series plots given the exact same data, but with different time dimensions. The project champion or process owner might come to a different conclusion depending on which graph he is shown.

Figure 1: Same Data but Different Time Dimensions

Start-based versus End-based Metrics

Typically, businesses prefer end-based metrics because performance is locked once the transactions are completed. Businesses prefer this because start-based metrics appear to change as older transactions complete their cycles. In the preceding example, the value for 123 North Street (-7 percent) would not be known until June and consequently appears to “change” the plotted value for January after the fact (i.e., going from a null value to -7 percent). Because financial performance is based on the business completed in a prior month or quarter, businesses almost always prefer end-based metrics.

The problem with end-based metrics is that if a project team implements an improvement on April 15th to reduce the percent difference metric it might appear that the project team made things worse.

Figure 2: Reducing the Percent Difference Metric

This is not the case since transactions subject to the improvement have not yet registered, but this might not be apparent to the uninformed.

0 comments:

Post a Comment