1. In general, a Six Sigma Black Belt should be quantitatively oriented.

2. With minimal guidance, the Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to use data to convert broad generalizations into actionable goals.

3. The Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to make the business case for attempting to accomplish these goals.

4. The Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to develop detailed plans for achieving these goals.

5. The Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to measure progress towards the goals in terms meaningful to customers and leaders.

6. The Six Sigma Black Belt should know how to establish control systems for maintaining the gains achieved through Six Sigma.

7. The Six Sigma Black Belt should understand and be able to communicate the rationale for continuous improvement, even after initial goals have been accomplished.

8. The Six Sigma Black Belt should be familiar with research that quantifies the benefits firms have obtained from Six Sigma.

9. The Six Sigma Black Belt should know or be able to find the PPM rates associated with different sigma levels (e.g., Six Sigma = 3.4 PPM)

10. The Six Sigma Black Belt should know the approximate relative cost of poor quality associated with various sigma levels (e.g., three sigma firms report 25% COPQ).

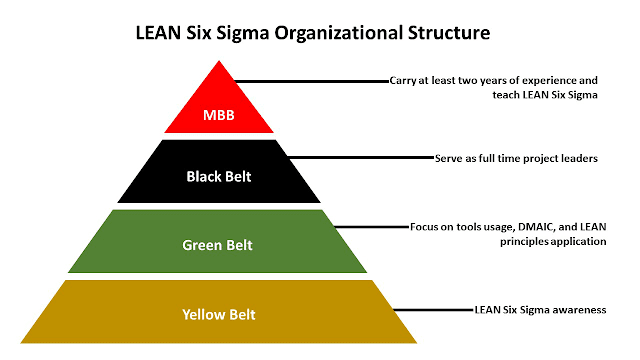

11. The Six Sigma Black Belt should understand the roles of the various people involved in change (senior leader, champion, mentor, change agent, technical leader, team leader, facilitator).

12. The Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to design, test, and analyze customer surveys.

13. The Six Sigma Black Belt should know how to quantitatively analyze data from employee and customer surveys. This includes evaluating survey reliability and validity as well as the differences between surveys.

14. Given two or more sets of survey data, the Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to determine if there are statistically significant differences between them.

15. The Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to quantify the value of customer retention.

16. Given a partly completed QFD matrix, the Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to complete it.

17. The Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to compute the value of money held or invested over time, including present value and future value of a fixed sum.

18. The Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to compute PV and FV values for various compounding periods.

19. The Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to compute the break even point for a project.

20. The Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to compute the net present value of cash flow streams, and to use the results to choose among competing projects.

21. The Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to compute the internal rate of return for cash flow streams and to use the results to choose among competing projects.

22. The Six Sigma Black Belt should know the COPQ rationale for Six Sigma, i.e., he should be able to explain what to do if COPQ analysis indicates that the optimum for a given process is less than Six Sigma.

23. The Six Sigma Black Belt should know the basic COPQ categories and be able to allocate a list of costs to the correct category.

24. Given a table of COPQ data over time, the Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to perform a statistical analysis of the trend.

25. Given a table of COPQ data over time, the Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to perform a statistical analysis of the distribution of costs among the various categories.

26. Given a list of tasks for a project, their times to complete, and their precedence relationships, the Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to compute the time to completion for the project, the earliest completion times, the latest completion times and the slack times. He should also be able to identify which tasks are on the critical path.

27. Give cost and time data for project tasks, the Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to compute the cost of normal and crash schedules and the minimum total cost schedule.

28. The Six Sigma Black Belt should be familiar with the basic principles of benchmarking.

29. The Six Sigma Black Belt should be familiar with the limitations of benchmarking.

30. Given an organization chart and a listing of team members, process owners, and sponsors, the Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to identify projects with a low probability of success.

31. The Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to identify measurement scales of various metrics (nominal, ordinal, etc).

32. Given a metric on a particular scale, the Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to determine if a particular statistical method should be used for analysis.

33. Given a properly collected set of data, the Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to perform a complete measurement system analysis, including the calculation of bias, repeatability, reproducibility, stability, discrimination (resolution) and linearity.

34. Given the measurement system metrics, the Six Sigma Black Belt should know whether or not a given measurement system should be used on a given part or process.

35. The Six Sigma Black Belt should know the difference between computing sigma from a data set whose production sequence is known and from a data set whose production sequence is not known.

36. Given the results of an AIAG Gage R&R study, the Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to answer a variety of questions about the measurement system.

37. Given a narrative description of "as-is" and "should-be" processes, the Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to prepare process maps.

38. Given a table of raw data, the Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to prepare a frequency tally sheet of the data, and to use the tally sheet data to construct a histogram.

39. The Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to compute the mean and standard deviation from a grouped frequency distribution.

40. Given a list of problems, the Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to construct a Pareto Diagram of the problem frequencies.

41. Given a list which describes problems by department, the Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to construct a Cross tabulation and use the information to perform a Chi-square analysis.

42. Given a table of x and y data pairs, the Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to determine if the relationship is linear or non-linear.

43. The Six Sigma Black Belt should know how to use non-linearity’s to make products or processes more robust.

44. The Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to construct and interpret a run chart when given a table of data in time-ordered sequence. This includes calculating run length, number of runs and quantitative trend evaluation.

45. When told the data are from an exponential or Erlang distribution the Six Sigma Black Belt should know that the run chart is preferred over the standard X control chart.

46. Given a set of raw data the Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to identify and compute two statistical measures each for central tendency, dispersion, and shape.

47. Given a set of raw data, the Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to construct a histogram.

48. Given a stem & leaf plot, the Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to reproduce a sample of numbers to the accuracy allowed by the plot.

49. Given a box plot with numbers on the key box points, the Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to identify the 25th and 75th percentile and the median.

50. The Six Sigma Black Belt should know when to apply enumerative statistical methods, and when not to.

51. The Six Sigma Black Belt should know when to apply analytic statistical methods, and when not to.

52. The Six Sigma Black Belt should demonstrate a grasp of basic probability concepts, such as the probability of mutually exclusive events, of dependent and independent events, of events that can occur simultaneously, etc.

53. The Six Sigma Black Belt should know factorials, permutations and combinations, and how to use these in commonly used probability distributions.

54. The Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to compute expected values for continuous and discrete random variables.

55. The Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to compute univariate statistics for samples.

56. The Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to compute confidence intervals for various statistics.

57. The Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to read values from a cumulative frequency ogive.

58. The Six Sigma Black Belt should be familiar with the commonly used probability distributions, including: hyper geometric, binomial, Poisson, normal, exponential, chi-square, Student's t, and F.

59. Given a set of data the Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to correctly identify which distribution should be used to perform a given analysis, and to use the distribution to perform the analysis.

60. The Six Sigma Black Belt should know that different techniques are required for analysis depending on whether a given measure (e.g., the mean) is assumed known or estimated from a sample. The Six Sigma Black Belt should choose and properly use the correct technique when provided with data and sufficient information about the data.

61. Given a set of sub grouped data, the Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to select and prepare the correct control charts and to determine if a given process is in a state of statistical control.

62. The above should be demonstrated for data representing all of the most common control charts.

63. The Six Sigma Black Belt should understand the assumptions that underlie ANOVA, and be able to select and apply a transformation to the data.

64. The Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to identify which cause on a list of possible causes will most likely explain a non-random pattern in the regression residuals.

65. If shown control chart patterns, the Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to match the control chart with the correct situation (e.g., an outlier pattern vs. a gradual trend matched to a tool breaking vs. a machine gradually warming up).

66. The Six Sigma Black Belt should understand the mechanics of PREControl.

67. The Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to correctly apply EWMA charts to a process with serial correlation in the data.

68. Given a stable set of sub grouped data, the Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to perform a complete Process Capability Analysis. This includes computing and interpreting capability indices, estimating the % failures, control limit calculations, etc.

69. The Six Sigma Black Belt should demonstrate an awareness of the assumptions that underlie the use of capability indices.

70. Given the results of a replicated 22 full-factorial experiment, the Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to complete the entire ANOVA table.

71. The Six Sigma Black Belt should understand the basic principles of planning a statistically designed experiment. This can be demonstrated by critiquing various experimental plans with or without shortcomings.

72. Given a "clean" experimental plan, the Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to find the correct number of replicates to obtain a desired power.

73. The Six Sigma Black Belt should know the difference between the various types of experimental models (fixed-effects, random-effects, mixed).

74. The Six Sigma Black Belt should understand the concepts of randomization and blocking.

75. Given a set of data, the Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to perform a Latin Square analysis and interpret the results.

76. Ditto for one way ANOVA, two way ANOVA (with and without replicates), full and fractional factorials, and response surface designs.

77. Given an appropriate experimental result, the Six Sigma Black Belt should be able to compute the direction of steepest ascent.

78. Given a set of variables each at two levels, the Six Sigma Black Belt can determine the correct experimental layout for a screening experiment using a saturated design.

79. Given data for such an experiment, the Six Sigma Black Belt can identify which main effects are significant and state the effect of these factors.

80. Given two or more sets of responses to categorical items (e.g.,customer survey responses categorized as poor, fair, good, excellent),the Six Sigma Black Belt will be able to perform a Chi-Square test to determine if the samples are significantly different.

81. The Six Sigma Black Belt will understand the idea of confounding and be able to identify which two factor interactions are confounded with the significant main effects.

82. The Six Sigma Black Belt will be able to state the direction of steepest ascent from experimental data.

83. The Six Sigma Black Belt will understand fold over designs and be able to identify the fold over design that will clear a given alias.

84. The Six Sigma Black Belt will know how to augment a factorial design to create a composite or central composite design.

85. The Six Sigma Black Belt will be able to evaluate the diagnostics for an experiment.

86. The Six Sigma Black Belt will be able to identify the need for a transformation in y and to apply the correct transformation.

87. Given a response surface equation in quadratic form, the Six Sigma Black Belt will be able to compute the stationary point.

88. Given data (not graphics), the Six Sigma Black Belt will be able to determine if the stationary point is a maximum, minimum or saddle point.

89. The Six Sigma Black Belt will be able to use a quadratic loss function to compute the cost of a given process.

90. The Six Sigma Black Belt will be able to conduct simple and multiple linear regression.

91. The Six Sigma Black Belt will be able to identify patterns in residuals from an improper regression model and to apply the correct remedy.

92. The Six Sigma Black Belt will understand the difference between regression and correlation studies.

93. The Six Sigma Black Belt will be able to perform chi-square analysis of contingency tables.

94. The Six Sigma Black Belt will be able to compute basic reliability statistics (mtbf, availability, etc.).

95. Given the failure rates for given subsystems, the Six Sigma Black Belt will be able to use reliability apportionment to set mtbf goals.

96. The Six Sigma Black Belt will be able to compute the reliability of series, parallel, and series-parallel system configurations.

97. The Six Sigma Black Belt will demonstrate the ability to create and read an FMEA analysis.

98. The Six Sigma Black Belt will demonstrate the ability to create and read a fault tree.

99. Given distributions of strength and stress, the Six Sigma Black Belt will be able to compute the probability of failure.

100. The Six Sigma Black Belt will be able to apply statistical tolerance to set tolerances for simple assemblies. He will know how to compare statistical tolerances to so-called "worst case" tolerance.

101. The Six Sigma Black Belt will be aware of the limits of the Six Sigma approach.