Many organizations have attempted to implement some form of project management into their organization with different degrees of success. Implementation success varies by the awareness and method to which the program was introduced, often leaving many feeling that LSS is just another flavor of the month. Once the awareness of the benefits that LSS can provide has been created, there is often another huddle to conquer related to, how do non-Belt team members understand what you are talking about. Many of us have often heard, “I have no idea what you mean by a Kaizen event, value-add activities, muda, or fishbone diagrams,” and many have a difficult time participating due to “living in the weeds” of the LSS vocabulary. Other practitioners in new LSS healthcare environments are faced with the veteran nursing director who has seen and heard it all and does not buy into the positive effects of applying a LSS approach.

Wednesday, 31 May 2017

Tuesday, 30 May 2017

IT4IT - The Basis for a Toolchain Architecture

If everything is to be processed faster, better and at a lower cost in the future, automation and the smooth integration of functions and processes will not be a thing of the past. The agile methods, which are currently very vogue, are also aimed at. However, I would not like to deny that this is primarily a question of cultural aspects. In this article, however, I would like to highlight the effects on the tool landscape in companies.

IT services are complex structures, sometimes complicated. In order for an IT service to fly in its end-to-end view, many specialists and external providers are required to make their contribution. There is virtually no one in a company that knows exactly how IT services are made and assembled by a particular IT service. Every function involved brings in his special knowledge and organizes himself around his responsibility.

The IT organizations sit in their silo towers and settle "their" world is long known. The cultural clashes, which are warned in the demand for better cooperation, does not come by chance. This also begins with the strategy and planning of new IT projects. At the very beginning of an idea, the view of a later IT service is not just nebulised - it is often not even existing. The idea is then poured into solutions and, depending on the involved teams, then passed from Silo Tower to Silo Tower. Each silo is committed to integrating the new solution into its world and landscape and to supplement it with data and functions until ultimately it is made available to the impatient user after several hurdles in a productive environment.

Until now this was not really a problem. Inadequacies could be caught and cleansed locally between the adjacent teams. One always remains guilty of each other. But now the wind has turned. The Unicorns make it: the clock rate must be drastically increased. New operating models with cloud services are now part of the portfolio. New methods like DevOps, Continuous Integration and Delivery are announced. As the existing teams are not able to take over the work they have done, they go to the factory with dedicated teams and build their own worlds - one could also say "new silos".

IT services are complex structures, sometimes complicated. In order for an IT service to fly in its end-to-end view, many specialists and external providers are required to make their contribution. There is virtually no one in a company that knows exactly how IT services are made and assembled by a particular IT service. Every function involved brings in his special knowledge and organizes himself around his responsibility.

The IT organizations sit in their silo towers and settle "their" world is long known. The cultural clashes, which are warned in the demand for better cooperation, does not come by chance. This also begins with the strategy and planning of new IT projects. At the very beginning of an idea, the view of a later IT service is not just nebulised - it is often not even existing. The idea is then poured into solutions and, depending on the involved teams, then passed from Silo Tower to Silo Tower. Each silo is committed to integrating the new solution into its world and landscape and to supplement it with data and functions until ultimately it is made available to the impatient user after several hurdles in a productive environment.

Until now this was not really a problem. Inadequacies could be caught and cleansed locally between the adjacent teams. One always remains guilty of each other. But now the wind has turned. The Unicorns make it: the clock rate must be drastically increased. New operating models with cloud services are now part of the portfolio. New methods like DevOps, Continuous Integration and Delivery are announced. As the existing teams are not able to take over the work they have done, they go to the factory with dedicated teams and build their own worlds - one could also say "new silos".

Any initiative with new tools and processes

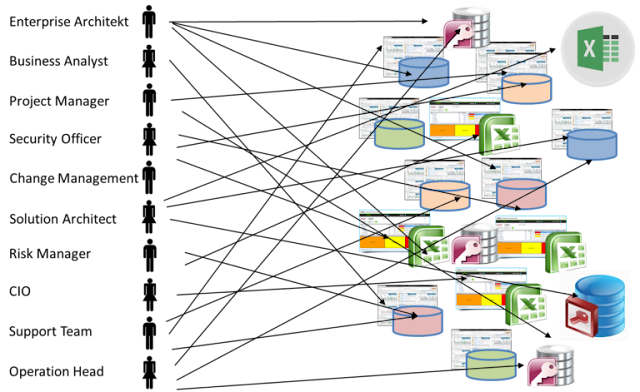

And this is one of the cornerstones of today's IT operations. Each organizational unit today has its own tools with often isolated data sets. Not infrequently in IT organizations more than 100 tools and tens of Excel tables are in use with a multiple of interfaces which are more or less documented. An overview of the tools is generally not available and the quality of the data is in many cases doubtful. Each team implements «its» processes according to their own needs and obtains the tools that ideally meet their requirements. The data are not available, and certainly not transparent or secured.

100 and more tools are the rule

.

What is not conceivable in the manufacture of products in the business is in the IT. There is no comprehensive data structure and information chain in planning, implementation, implementation and operation. If certain roles such as Project Manager, Change Manager or Solution Architect want to know more about the manufacturing process, then he does not have a clear view of where and what data is reliable. It is not uncommon for him to ask them in the organization. Even after that, he is not really sure whether he can rely on reliable data. The fact that such constellations ultimately lead to surprises, that the original idea about the various stations up to the operation is no longer identical, may not really be surprising.

Who has what data?

If automation is the key to continuous integration and deployment, this type of IT operating model is not enough. And though the various guardians try to keep their tools with interfaces and APIs in the game in order to allow a toolchain. Faster, better and above all cheaper it will not.

It takes a tool governance and a tool architecture to meet the demands of the future. It has to be over, that each team and every specialist procures the best tool for him and collects for himself data, which have no further benefit in the enterprise. IT4IT can play a good foundation and reference here.

IT4IT TM is not simply a new process model, which attempts to repress the established and more or less well-implemented frameworks such as ITIL® or COBIT®. It is rather a missing today to the well-known frameworks with detailed descriptions for an integrated IT operating model as the necessary IT functionality is designed, procured and implemented. IT4IT TM is based on the following four pillars:

- Data & Information Model - a data entity model with all core data objects, attributes, and relationships

- Functional model - the definition of the central IT management systems for the management of the data and the automation

- Integration model - for linking processes, data and systems to deliver value

- Service model - The backbone of the value chain model is based on the service LifeCycle

IT4IT - The four pillars

IT4IT can now be a good starting point for creating a viable toolchain architecture. Although IT4IT has not yet been definitively defined in all the details, there is a function and information structure geared to the required added value.

IT4IT - The four contiguous value streams

Sunday, 28 May 2017

The History of PRINCE2

PRINCE2 today is the de facto project management standard. The UK government in the 1980s demanded a solution to common project problems. They were struggling to deliver on time, under budget, within scope and up to quality. Like many private companies, they wanted a method focused on deliverables.

While PRINCE2 was formalised by the UK government, it was inspired by a private sector framework. Simpact Systems Ltd developed PROMPT, which contained a system development module called PROMPT II. PROMPT stood for Project Resource Organisation Management and Planning Techniques. Simpact developed PROMPT in response to computer projects overrunning on time and budget.

To make IT projects more manageable, the PROMPT lifecycle broke them into phases:

The UK government, looking for an IT project management method, licensed the use of PROMPT from Simpact. The Central Computer and Telecommunications Agency only fully implemented the PROMPT II module, and adjusted it to create a new standard. Like PROMPT II, it was meant for IT project management.

Their variation of PROMPT II was named ‘PRINCE’ in April 1989. Originally, it stood for ‘PROMPT II IN the CCTA Environment’. Civil servants later changed the acronym to ‘PRojects IN Controlled Environments’. Changes from PROMPT II introduced Critical Path Analysis and project managers.

PRINCE was released into the public domain in 1990, where it was more widely adopted. The UK government used it for major non-IT projects and it was taking hold in the private sector. However, the method had a reputation for being too rigid and unsuited to smaller projects.

PRINCE2 was developed in consultation with about 150 European organisations. This virtual committee agreed on what they considered best practice. Along with the general framework of PRINCE, this advice formed PRINCE2.

PRINCE2 is a generic project management framework, unlike PRINCE, which was designed for IT projects and adopted by other industries. To be suitable for every project, PRINCE2 has to be scaled down from PRINCE. For example, PRINCE demanded separate Business Assurance, Technical Assurance and User Assurance Coordinators. PRINCE2 doesn’t call for this because it’s too demanding for smaller projects.

The global market responded well to this new framework. PRINCE2 retains its focus on the final product, but is more tailorable to different project environments. Because of this, PRINCE2 has become the de facto project management standard.

PRINCE2 went through a number of revisions starting in 1998. In 2002, the international user community started consulting on PRINCE2 updates. The biggest revision, in 2009, made PRINCE2 more simple and customisable. The 2009 version also introduced the seven principles. PRINCE2’s 2013 ownership change to AXELOS Ltd led to PRINCE2 Agile. It’s thanks to the 2009 revision that PRINCE2 is now simple and light enough to make this newer course not just possible, but intuitive.

AXELOS published its next major update in 2017. The new guidance focuses on scalability and flexibility. PRINCE2 from the beginning supported and encouraged tailoring. The 2017 update clarifies the bare minimum for a project to qualify as PRINCE2. It then shows examples, hints and tips about how to adjust these core principles to your project.

Despite being major revisions, the name PRINCE2 hasn’t changed. Instead of referring to PRINCE3, ‘PRINCE2:2009 Refresh’ and ‘PRINCE2 2017 Update’ were chosen because the core principles behind PRINCE2 remain the same.

PRINCE2, time-tested but updated, has proven its value over the decades. See the list of PRINCE2 courses we have on offer and you can be qualified in the de facto project management standard. For any questions or queries, please visit our contact page.

1975 – PROMPT and the Origins of PRINCE2

While PRINCE2 was formalised by the UK government, it was inspired by a private sector framework. Simpact Systems Ltd developed PROMPT, which contained a system development module called PROMPT II. PROMPT stood for Project Resource Organisation Management and Planning Techniques. Simpact developed PROMPT in response to computer projects overrunning on time and budget.

To make IT projects more manageable, the PROMPT lifecycle broke them into phases:

- Initiation

- Specification

- Design

- Development

- Installation

- Operation

1989 – PRINCE, Laying the Groundwork for PRINCE2

The UK government, looking for an IT project management method, licensed the use of PROMPT from Simpact. The Central Computer and Telecommunications Agency only fully implemented the PROMPT II module, and adjusted it to create a new standard. Like PROMPT II, it was meant for IT project management.

Their variation of PROMPT II was named ‘PRINCE’ in April 1989. Originally, it stood for ‘PROMPT II IN the CCTA Environment’. Civil servants later changed the acronym to ‘PRojects IN Controlled Environments’. Changes from PROMPT II introduced Critical Path Analysis and project managers.

PRINCE was released into the public domain in 1990, where it was more widely adopted. The UK government used it for major non-IT projects and it was taking hold in the private sector. However, the method had a reputation for being too rigid and unsuited to smaller projects.

1996 – PRINCE2 Is Published

PRINCE2 was developed in consultation with about 150 European organisations. This virtual committee agreed on what they considered best practice. Along with the general framework of PRINCE, this advice formed PRINCE2.

PRINCE2 is a generic project management framework, unlike PRINCE, which was designed for IT projects and adopted by other industries. To be suitable for every project, PRINCE2 has to be scaled down from PRINCE. For example, PRINCE demanded separate Business Assurance, Technical Assurance and User Assurance Coordinators. PRINCE2 doesn’t call for this because it’s too demanding for smaller projects.

The global market responded well to this new framework. PRINCE2 retains its focus on the final product, but is more tailorable to different project environments. Because of this, PRINCE2 has become the de facto project management standard.

2009 – A major revision

PRINCE2 went through a number of revisions starting in 1998. In 2002, the international user community started consulting on PRINCE2 updates. The biggest revision, in 2009, made PRINCE2 more simple and customisable. The 2009 version also introduced the seven principles. PRINCE2’s 2013 ownership change to AXELOS Ltd led to PRINCE2 Agile. It’s thanks to the 2009 revision that PRINCE2 is now simple and light enough to make this newer course not just possible, but intuitive.

2017 – The second major revision

AXELOS published its next major update in 2017. The new guidance focuses on scalability and flexibility. PRINCE2 from the beginning supported and encouraged tailoring. The 2017 update clarifies the bare minimum for a project to qualify as PRINCE2. It then shows examples, hints and tips about how to adjust these core principles to your project.

Despite being major revisions, the name PRINCE2 hasn’t changed. Instead of referring to PRINCE3, ‘PRINCE2:2009 Refresh’ and ‘PRINCE2 2017 Update’ were chosen because the core principles behind PRINCE2 remain the same.

PRINCE2, time-tested but updated, has proven its value over the decades. See the list of PRINCE2 courses we have on offer and you can be qualified in the de facto project management standard. For any questions or queries, please visit our contact page.

Thursday, 18 May 2017

Productivity and Employment

When talking about Lean and Six Sigma, people often associate them with improved productivity. Other times they associate them with their possible consequences: high profitability or loss of jobs. In today’s economic environment, many people are concerned with the potential trade-off between productivity improvement and employment. But is there such a trade-off relationship?

The report has a lot of useful data and analyses, most of which I won’t discuss here. What interested me was how they analyzed the relationship between productivity and employment growth.

In their Executive Summary, the authors state

“Since 1929, every ten-year rolling period except one has recorded increases in both US productivity and employment. And even on a rolling annual basis, 69 percent of periods have delivered both productivity and jobs growth (Exhibit E6).”

On page 27, “Box 2. Long-term economic growth through higher productivity and more jobs” the authors provide 3 reasons why higher productivity can help create jobs.

1. Lower prices and more consumer savings boost demand for goods and services

2. Higher quality and customer value boost demand

3. Global competitiveness necessary to attract and maintain jobs

They also argue that “the perceived trade-off between productivity growth and employment growth is a temporary phenomenon. More than two-thirds of the years since 1929 have seen positive gains in both productivity and employment (Exhibit 15). If we look at quarters, employment growth followed gains in productivity 71 percent of quarters since 1947 (Exhibit 16).”

What does their data analysis tell you?

Not much, I have to say. Why? See the figure below.

The report has a lot of useful data and analyses, most of which I won’t discuss here. What interested me was how they analyzed the relationship between productivity and employment growth.

In their Executive Summary, the authors state

“Since 1929, every ten-year rolling period except one has recorded increases in both US productivity and employment. And even on a rolling annual basis, 69 percent of periods have delivered both productivity and jobs growth (Exhibit E6).”

On page 27, “Box 2. Long-term economic growth through higher productivity and more jobs” the authors provide 3 reasons why higher productivity can help create jobs.

1. Lower prices and more consumer savings boost demand for goods and services

2. Higher quality and customer value boost demand

3. Global competitiveness necessary to attract and maintain jobs

They also argue that “the perceived trade-off between productivity growth and employment growth is a temporary phenomenon. More than two-thirds of the years since 1929 have seen positive gains in both productivity and employment (Exhibit 15). If we look at quarters, employment growth followed gains in productivity 71 percent of quarters since 1947 (Exhibit 16).”

What does their data analysis tell you?

Not much, I have to say. Why? See the figure below.

I could draw the same conclusion with this figure as they did with Exhibit 6 or 15. But I won’t. The reason is that the 2 series of data (Pro and Emp) used to generate this figure were completely independent of each other — there is no relationship at all. In other words, the figure shows what we would expect from random data of 2 independent variables.

To create 80 random values of Pro, I simply set a 15% probability of being negative (down) and 85% positive (up) and let the Excel function [=Rand()-0.15] do the rest. Similarly, 80 values of Emp were randomly generated with a 25% probability of negative and 75% of positive. The two lists are paired as if they came from the same period. The figure shows how often they are both up or down or different in each period. Although the figure shows one sample of randomly generated numbers, other simulated results more or less show the same pattern.

Now I hope you see the analysis presented in the report is as valuable as a relationship I could draw from a random sample of data of two independent variables — not much.

The same lesson can be learned from their Exhibit 16. What ADDITIONAL knowledge do we gain by knowing that 71% of the time both productivity and employment are gains, without knowing what is expected by chance alone based on individual probability? Anytime I have two independent variables with a probability of 0.8-0.9 being positive, I would expect them both being positive about 70% of the time.

To create 80 random values of Pro, I simply set a 15% probability of being negative (down) and 85% positive (up) and let the Excel function [=Rand()-0.15] do the rest. Similarly, 80 values of Emp were randomly generated with a 25% probability of negative and 75% of positive. The two lists are paired as if they came from the same period. The figure shows how often they are both up or down or different in each period. Although the figure shows one sample of randomly generated numbers, other simulated results more or less show the same pattern.

Now I hope you see the analysis presented in the report is as valuable as a relationship I could draw from a random sample of data of two independent variables — not much.

The same lesson can be learned from their Exhibit 16. What ADDITIONAL knowledge do we gain by knowing that 71% of the time both productivity and employment are gains, without knowing what is expected by chance alone based on individual probability? Anytime I have two independent variables with a probability of 0.8-0.9 being positive, I would expect them both being positive about 70% of the time.

Friday, 5 May 2017

3 Common Pitfalls to Avoid with PRINCE2

Although project success rates are growing, project managers still struggle with many common pitfalls. Here are some of the ways PRINCE2 can prepare you for them.

Every good project has a clear goal. It’s easier to assign work and correct problems when you know the end goal. Along with a clear scope, it also makes it easier to define project success. Even small changes like changing the colour of a logo create delays. When these little changes go unchecked, they can ruin projects. Here are some of PRINCE2’s tools for staying on scope:

Micromanagement tends to be more prevalent among budding managers. However, managers at every level are susceptible to it, and the results are never good. Project teams should be able to get immersed in their work. Instead of fostering a ‘babysitting’ corporate culture, consider this:

Project managers are eager to make clients happy with a quick product delivery, but this often leads to overambitious estimates. It’s easier to form and stick to a realistic deadline with these tools:

1. Unclear scope

Every good project has a clear goal. It’s easier to assign work and correct problems when you know the end goal. Along with a clear scope, it also makes it easier to define project success. Even small changes like changing the colour of a logo create delays. When these little changes go unchecked, they can ruin projects. Here are some of PRINCE2’s tools for staying on scope:

- Project Initiation Document (PID) – As the name suggests, this document is part of the Initiation stage. A complete PID will outline the project’s objectives, scope and exclusions. With these three documented, you can not only define the scope, but also manage scope creep.

- Change control – PRINCE2 uses the term ‘issue’ to describe unplanned events that require management intervention. You can’t stop issues from arising, but you can control how they’re handled. PRINCE2 has five steps to handling issues and keeping projects on-scope. This process is abbreviated to CEPDI:

- Capture: Determine type of issue

- Examine: Assess the impact of the issue on the project objectives

- Propose: Propose actions to take

- Decide: Someone decides to approve or reject the recommended solution

- Implement: Put the recommended solution in action

2. Micromanagement

Micromanagement tends to be more prevalent among budding managers. However, managers at every level are susceptible to it, and the results are never good. Project teams should be able to get immersed in their work. Instead of fostering a ‘babysitting’ corporate culture, consider this:

- Manage by exception – One of PRINCE2’s 7 core principles. It means senior managers are only alerted to major process deviations. This not only gives the project team more breathing room, but it also helps senior managers prioritise their time.

- Communication Management Strategy (CMS) – This document on how you’ll communicate with stakeholders was brought up in the previous blog, in reference to sponsors. Since everyone in the project team is also a stakeholder, the CMS should account for them. With regular meetings, the project team and team manager won’t have to spend as much time updating you. Instead, they can raise issues without disruption.

3. Unrealistic timelines

Project managers are eager to make clients happy with a quick product delivery, but this often leads to overambitious estimates. It’s easier to form and stick to a realistic deadline with these tools:

- Project Plan – Part of the Project Initiation Document (PID). It details the start and end points of the project’s milestones/stages, and control points for these. By breaking the stages down, it’s easier to judge the length of the project. It will be less tempting to underestimate the project length when the stages are laid out in front of you.

- Project Assurance – This is where manage by exception and Change Control come in. After the first delivery stage, you may no longer agree with your original timeline. You can save a new version of your Project Plan with new information and estimates. Project Assurance can help devise these new estimates. Better yet, senior managers and sponsors can lend their support to get the project back on track.

Monday, 1 May 2017

A Parallel Process View for Information Technology

The value and impact that a solid Design for Six Sigma (DFSS) approach can bring to an IT business is well known. While many organizations understand the relationship between DFSS and their own project management approach, what they often miss is attention to the foundational concepts of Lean and DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control) to ensure that DFSS is applied most effectively.

The IT practitioners’ situation is uniquely challenging in that they must see their world from two very different perspectives:

Interestingly, both views of the organization distill to one fundamental concept – the value stream, applied in two different ways. And of course, anyone with even limited experience with Lean or Six Sigma will recognize this concept as a critical element of both process management and process improvement.

From a simplistic point of view, the IT function exists to make the core business processes (marketing, developing, selling, producing and distributing a product or service) more successful. In fact, whether providing its wares to external customers or supporting the management systems and operations of its own organization, the IT function is an operation unto itself. IT’s processes provide products (applications, hardware, networks) and services (security, maintenance, support, technology consulting) that create value for its customers (internal and external).

Users of IT products and services seem to demonstrate a unique lack of restraint when expressing feedback relative to the quality (cycle time, capability and cost) of their customer experience. As a result, when introduced to the utility of the Six Sigma approach, many IT managers immediately embrace the notion that DFSS is the most useful application of Six Sigma to enhance their current project management discipline and delivers better applications, networks or hardware faster and at a lower cost. In executing this well-conceived notion, IT organizations are quick to realize the importance of understanding the customer’s value stream and both the latent and expressed requirements through the effective analysis of use cases and language data. By this point, a typical DFSS project will have facilitated completion of the requirements-gathering component of a project management discipline by executing the Define and Measure phases of the DMADV (Define, Measure, Analyze, Design, Verify) approach.

But the IT dilemma becomes more acute in the Analyze phase of the DMADV cycle when a project team must determine which combination of features and levels of functionality will best satisfy the requirements of the customer(s) in terms of quality, cycle time and cost. To make matters more difficult, the project team must have some way to objectively evaluate cost and quality both in terms of the initial release as well as ongoing support. The DFSS project team must optimize the natural conflict between the need to satisfy the customer requirements and the capability of the complex IT architecture – the combination of people, hardware, networks and management systems that defines the IT organization. Many useful tools exist within Six Sigma to conquer this challenge. They range from the very simple (brainstorming and prioritization matrices) to the very complex (statistical experimentation and simulations). But no objective assessment of the alternatives is possible without quantitatively measuring the various value streams that exist within the IT organization. And furthermore, no meaningful project plan can be developed without the same IT process information.

This brings the subject back to the dual process view that characterizes the IT environment. For any given project, a DFSS project team must understand the value stream of its customers. This is often facilitated by some combination of the voice of the customer tools from the DMADV roadmap and the data provided by the customer’s own process management system. (Any effective process design should include the ability to document, measure, monitor, report and control the critical aspects of that process. IT software, hardware and network development projects must take those process management needs into account when participating in the design of new processes. In addition, the new process should be flexible enough to change its management system when critical process characteristics change.)

But this understanding of the customer value stream is not enough. The IT organization must document, measure and control its own value streams if DFSS projects are to be successful. This view then completes the Six Sigma management system within IT by addressing the three process dimensions upon which the Six Sigma methodology is built:

Inevitably the dilemma of the Analyze phase of the DMADV cycle begs the question: “If we need process management data to execute DMADV projects but we have urgent needs to apply DMADV tools to new projects, do we need to implement process management before applying DFSS in our project management system?” Fortunately, the answer is no. But understand that without an effective process management and improvement system the results of DFSS projects will necessarily be compromised. As a result, the Six Sigma deployment plan for an IT organization must account for the need to document, measure and – where applicable – manage and improve both types of value streams.

One important characteristic of Six Sigma is that no project is perfect and no set of data is perfect. This is particularly true in new Six Sigma deployments where the three process dimensions have not yet been adequately addressed. Choosing to apply DMADV to current or new projects without the benefit of a robust process management infrastructure is a viable strategy as long as there is an explicit plan to document, measure and control the critical value streams within the IT organization. The development of a mature process management system takes time and will ultimately require the participation of most, if not all, IT employees. The result, however, will be powerful as this view of the internal value streams will provide the organization with the basic understanding of Lean principles as it relates to value, waste and process performance measures (including quality, cycle time and cost). This internal process perspective will provide a foundation which will enhance the application of DMAIC to continuously improve internal processes and DMADV to optimize the effect of IT products and services on the customers which it supports.

In both service and manufacturing environments, the IT systems play an important role in determining the capacity, flexibility and capability of its customers’ processes. As a result, the IT organization is particularly suited to deployment of the three Six Sigma process dimensions. Recognizing the need to understand both internal value streams and customer value streams is an important first step to creating a successful Six Sigma deployment in IT.

The IT practitioners’ situation is uniquely challenging in that they must see their world from two very different perspectives:

- How the business uses their services.

- How IT provides services to the business.

Better Core Business Processes

From a simplistic point of view, the IT function exists to make the core business processes (marketing, developing, selling, producing and distributing a product or service) more successful. In fact, whether providing its wares to external customers or supporting the management systems and operations of its own organization, the IT function is an operation unto itself. IT’s processes provide products (applications, hardware, networks) and services (security, maintenance, support, technology consulting) that create value for its customers (internal and external).

Users of IT products and services seem to demonstrate a unique lack of restraint when expressing feedback relative to the quality (cycle time, capability and cost) of their customer experience. As a result, when introduced to the utility of the Six Sigma approach, many IT managers immediately embrace the notion that DFSS is the most useful application of Six Sigma to enhance their current project management discipline and delivers better applications, networks or hardware faster and at a lower cost. In executing this well-conceived notion, IT organizations are quick to realize the importance of understanding the customer’s value stream and both the latent and expressed requirements through the effective analysis of use cases and language data. By this point, a typical DFSS project will have facilitated completion of the requirements-gathering component of a project management discipline by executing the Define and Measure phases of the DMADV (Define, Measure, Analyze, Design, Verify) approach.

But the IT dilemma becomes more acute in the Analyze phase of the DMADV cycle when a project team must determine which combination of features and levels of functionality will best satisfy the requirements of the customer(s) in terms of quality, cycle time and cost. To make matters more difficult, the project team must have some way to objectively evaluate cost and quality both in terms of the initial release as well as ongoing support. The DFSS project team must optimize the natural conflict between the need to satisfy the customer requirements and the capability of the complex IT architecture – the combination of people, hardware, networks and management systems that defines the IT organization. Many useful tools exist within Six Sigma to conquer this challenge. They range from the very simple (brainstorming and prioritization matrices) to the very complex (statistical experimentation and simulations). But no objective assessment of the alternatives is possible without quantitatively measuring the various value streams that exist within the IT organization. And furthermore, no meaningful project plan can be developed without the same IT process information.

Back to the Dual Process View

This brings the subject back to the dual process view that characterizes the IT environment. For any given project, a DFSS project team must understand the value stream of its customers. This is often facilitated by some combination of the voice of the customer tools from the DMADV roadmap and the data provided by the customer’s own process management system. (Any effective process design should include the ability to document, measure, monitor, report and control the critical aspects of that process. IT software, hardware and network development projects must take those process management needs into account when participating in the design of new processes. In addition, the new process should be flexible enough to change its management system when critical process characteristics change.)

But this understanding of the customer value stream is not enough. The IT organization must document, measure and control its own value streams if DFSS projects are to be successful. This view then completes the Six Sigma management system within IT by addressing the three process dimensions upon which the Six Sigma methodology is built:

- Process management – document, measure, monitor and control internal processes.

- Process improvement – use the DMAIC cycle repetitively to continuously improve.

- Product/process design – apply DFSS (DMADV) to radically redesign internal processes or to create new products/services for customers.

Dilemma of the Analyze Phase

Inevitably the dilemma of the Analyze phase of the DMADV cycle begs the question: “If we need process management data to execute DMADV projects but we have urgent needs to apply DMADV tools to new projects, do we need to implement process management before applying DFSS in our project management system?” Fortunately, the answer is no. But understand that without an effective process management and improvement system the results of DFSS projects will necessarily be compromised. As a result, the Six Sigma deployment plan for an IT organization must account for the need to document, measure and – where applicable – manage and improve both types of value streams.

One important characteristic of Six Sigma is that no project is perfect and no set of data is perfect. This is particularly true in new Six Sigma deployments where the three process dimensions have not yet been adequately addressed. Choosing to apply DMADV to current or new projects without the benefit of a robust process management infrastructure is a viable strategy as long as there is an explicit plan to document, measure and control the critical value streams within the IT organization. The development of a mature process management system takes time and will ultimately require the participation of most, if not all, IT employees. The result, however, will be powerful as this view of the internal value streams will provide the organization with the basic understanding of Lean principles as it relates to value, waste and process performance measures (including quality, cycle time and cost). This internal process perspective will provide a foundation which will enhance the application of DMAIC to continuously improve internal processes and DMADV to optimize the effect of IT products and services on the customers which it supports.

In both service and manufacturing environments, the IT systems play an important role in determining the capacity, flexibility and capability of its customers’ processes. As a result, the IT organization is particularly suited to deployment of the three Six Sigma process dimensions. Recognizing the need to understand both internal value streams and customer value streams is an important first step to creating a successful Six Sigma deployment in IT.